|

Listen to this article

|

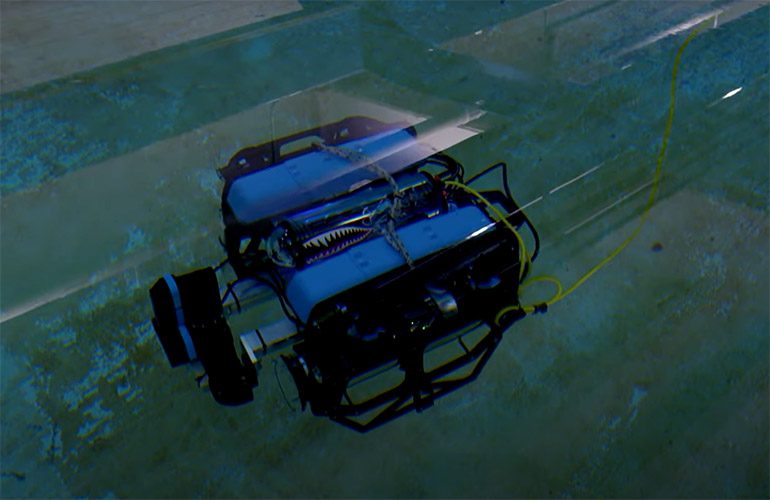

Stevens Institute of Technology’s BlueROV uses perception and mapping capabilities to operate without GPS, lidar, or radar underwater. Source: American Society of Mechanical Engineers

While defense spending is the source of many innovations in robotics and artificial intelligence, government policy usually takes a while to catch up to technological developments. Given all the attention on generative AI this year, October’s executive order on AI safety and security was “encouraging,” observed Dr. Brendan Englot, director of the Stevens Institute for Artificial Intelligence.

“There’s really very little regulation at this point, so it’s important to set common-sense priorities,” he told The Robot Report. “It’s a measured approach between unrestrained innovation for profit versus some AI experts wanting to halt all development.”

AI order covers cybersecurity, privacy, and national security

The executive order sets standards for AI testing, corporate information sharing with the government, and privacy and cybersecurity safeguards. The White House also directed the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to set “rigorous standards for extensive red-team testing to ensure safety before public release.”

The Biden-Harris administration’s order stated the goals of preventing the use of AI to engineer dangerous biological materials, to commit fraud, and to violate civil rights. In addition to developing “principles and best practices to mitigate the harms and maximize the benefits of AI for workers,” the administration claimed that it will promote U.S. innovation, competitiveness, and responsible government.

It also ordered the Department of Homeland Security to apply the standards to critical infrastructure sectors and to establish an AI Safety and Security Board. In addition, the executive order said the Department of Energy and the Department of Homeland Security must address AI systems’ threats to critical infrastructure and national security. It plans to develop a National Security Memorandum to direct further actions.

“It’s a common-sense set of measures to make AI more safe and trustworthy, and it captured a lot of different perspectives,” said Englot, an assistant professor at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, N.J. “For example, it called the general principle of watermarking as important. This will help resolve legal disputes over audio, video, and text. It might slow things a little bit, but the general public stands to benefit.”

Stevens Institute research touches multiple domains

“When I started with AI research, we began with conventional algorithms for robot localization and situational awareness,” recalled Englot. “At the Stevens Institute for Artificial Intelligence [SIAI], we saw how AI and machine learning could help.”

“We incorporated AI in two areas. The first was to enhance perception from limited information coming from sensors,” he said. “For example, machine learning could help an underwater robot with grainy, low-resolution images by building more descriptive, predictive maps so it could navigate more safely.”

“The second was to begin using reinforcement learning for decision making, for planning under uncertainty,” Englot explained. “Mobile robots need to navigate and make good decisions in stochastic, disturbance-filled environments, or where it doesn’t know the environment.”

Since stepping into the director role at the institute, Englot said he has seen work to apply AI to healthcare, finance, and the arts.

“We’re taking on larger challenges with multidisciplinary research,” he said. “AI can be used to enhance human decision making.”

Drive to commercialization could limit development paths

Generative AI such as ChatGPT has dominated headlines all year. The recent controversy around Sam Altman’s ouster and subsequent restoration as CEO of OpenAI demonstrates that the path to commercialization isn’t as direct as some assume, said Englot.

“There’s never a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model to go with emerging technologies,” he asserted. “Robots have done well in nonprofit and government development, and some have transitioned to commercial applications.”

“Others, not so much. Automated driving, for instance, has been dominated by the commercial sector,” Englot said. “It has some achievements, but it hasn’t totally lived up to its promise yet. The pressures from the rush to commercialization are not always a good thing for making technology more capable.”

AI needs more training, says Englot

To compensate for AI “hallucinations” or false responses to user questions, Englot said AI will be paired with model-based planning, simulation, and optimization frameworks.

“We’ve found that the generalized foundation model for GPT-4 is not as useful for specialized domains where tolerance for error is very low, such as for medical diagnosis,” said the Stevens Institute professor. “The degree of hallucination that’s acceptable for a chatbot isn’t here, so you need specialized training curated by experts.”

“For highly mission-critical applications, such as driving a vehicle, we should realize that generative AI may solve a problem, but it doesn’t understand all the rules, since they’re not hard-coded and it’s inferring from contextual information,” said Englot.

He recommended pairing generative AI with finite element models, computational fluid dynamics, or a well-trained expert in an iterative conversation. “We’ll eventually arrive at a powerful capability for solving problems and making more accurate predictions,” Englot predicted.

Collaboration to yield advances in design

The combination of generative AI with simulation and domain experts could lead to faster, more innovative designs in the next five years, said Englot.

“We’re already seeing generative AI-enabled Copilot tools in GitHub for creating code; we could soon see it used for modeling parts to be 3D-printed,” he said.

However, using robots to serve as the physical embodiments of AI in human-machine interactions could take more time because of safety concerns, he noted.

“The potential for harm from generative AI right now is limited to specific outputs — images, text, and audio,” Englot said. “Bridging the gap between AI and systems that can walk around and have physical consequences will take some engineering.”

Stevens Institute AI director still bullish on robotics

Generative AI and robotics are “a wide-open area of research right now,” said Englot. “Everyone is trying to understand what’s possible, the extent to which we can generalize, and how to generate data for these foundational models.”

While there is an embarrassment of riches on the Web for text-based models, robotics AI developers must draw from benchmark data sets, simulation tools, and the occasional physical resource such as Google’s “arm farm.” There is also the question of how generalizable data is across tasks, since humanoid robots are very different from drones, Englot said.

Legged robots such as Disney’s demonstration at iROS, which was trained to walk “with personality” through reinforcement learning, show that progress is being made.

Boston Dynamics spent years on designing, prototyping, and testing actuators to get to more efficient all-electric models, he said.

“Now, the AI component has come in by virtue of other companies replicating [Boston Dynamics’] success,” said Englot. “As with Unitree, ANYbotics, and Ghost Robotics trying to optimize the technology, AI is taking us to new levels of robustness.”

“But it’s more than locomotion. We’re a long way to integrating state-of-the-art perception, navigation, and manipulation and to get costs down,” he added. “The DARPA Subterranean Challenge was a great example of solutions to such challenges of mobile robotics. The Stevens Institute is conducting research on reliable underwater mobile manipulation funded by the USDA for sustainable offshore energy infrastructure and aquaculture.”

Tell Us What You Think!