|

Listen to this article

|

Cover of the 2024 U.S. robotics roadmap. Source: UC San Diego

Unlike China, Germany, or Japan, the U.S. doesn’t have a centralized industrial policy. The U.S. has a culture that uniquely encourages innovation, but a lack of strong coordination among academia, government, and industry affects the development and deployment of technologies such as robotics, according to the 2024 edition of “A Roadmap for U.S. Robotics: Robotics for a Better Tomorrow.”

The quadrennial set of recommendations is produced and sponsored by institutions led by the University of California, San Diego. The authors sent the latest edition to presidential campaigns, the AI Caucus in Congress, and the investment community, noted Henrik I . Christensen, main editor of the roadmap.

Henrik Christensen, UC San Diego

Christensen is the Qualcomm Chancellor’s Chair of Robot Systems and a distinguished professor of computer science at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at UC San Diego. He is also the director of the Contextual Robotics Institute, the Cognitive Robotics Laboratory, and the Autonomous Vehicle Laboratory.

In addition, Christensen is a serial entrepreneur, co-founding companies including Robust.AI. He is also an investor through firms such as ROBO Global, Calibrate Ventures, Interwoven, and Spring Mountain Capital.

The Robot Report spoke with Christensen about the latest “Roadmap for U.S. Robotics.”

Robotics roadmap gives a mixed review

How does this year’s roadmap compare with its predecessors?

Christensen: We’ve been doing this since 2009 and have aligned it to the federal elections. We did do a midterm report in 2022, and the current report card is mixed.

For instance, we’ve seen investments in laboratory automation and anticipated the workforce shortage because of demographics and changes in immigration policies. The COVID-19 pandemic also accelerated interest in e-commerce, supply chain automation, and eldercare.

The government support has been mixed. The National Robotics Initiative has sunset, and there have been no meetings of the Congressional Caucus on Robotics since 2019. Recently, we did have a robot showcase with the Congressional Caucus for AI.

With all of the recent attention on artificial intelligence, how does that help or hurt robotics?

Christensen: Some of the staffers of the AI caucus used to go to robotics caucus meetings. The AI initiative created about six years ago rolled up robotics, but in the end without any new funding for robotics.

Robotics, in many respects, is where AI meets reality. With the workforce shortage, there is a dire need for new robot technology to ensure growth of the U.S. economy.

We’ve heard that reshoring production is part of the answer, but it’s not clear that there must be a corresponding investment in R&D to make it happen. Without a National Robotics Initiative, there’s also no interagency coordination.

CMU co-hosted a Senate Robotics Showcase and Demo Day. Graduate student Richard Desatnik demonstrated a glove that remotely operated a soft robot on table. Source: Carnegie Mellon University

Christensen calls for more federal coordination

Between corporations, academic departments, and agencies such as DARPA and NASA, isn’t there already investment in robotics research and development?

Christensen: Multiple agencies sponsor robotics, in particular in the defense sector. The foundational research is mainly sponsored by the National Science Foundation, and the programs come across uncoordinated.

The roadmap isn’t asking for more money for robotics R&D; it’s recommending that available programs be better coordinated and directed toward more widespread industrial and commercial use.

While venture capital has been harder to get in the past few years, how would you describe the U.S. startup climate?

Christensen: We’re seeing a lot of excitement in robotics, with companies like Figure AI. While resources have gone into fundamental research, we need an full applications pipeline and grounded use cases.

Right now, most VCs are conservative, and interest rates have made it harder to get money. Last year, U.S. industrial automation was down 30%, which has been a challenge for robotics.

Why do you think that happened?

Christensen: It was a combination of factors, including COVID. Companies over-invested based on assumptions but then couldn’t invest in infrastructure. Investment in facilities is limited until we get better interest rates.

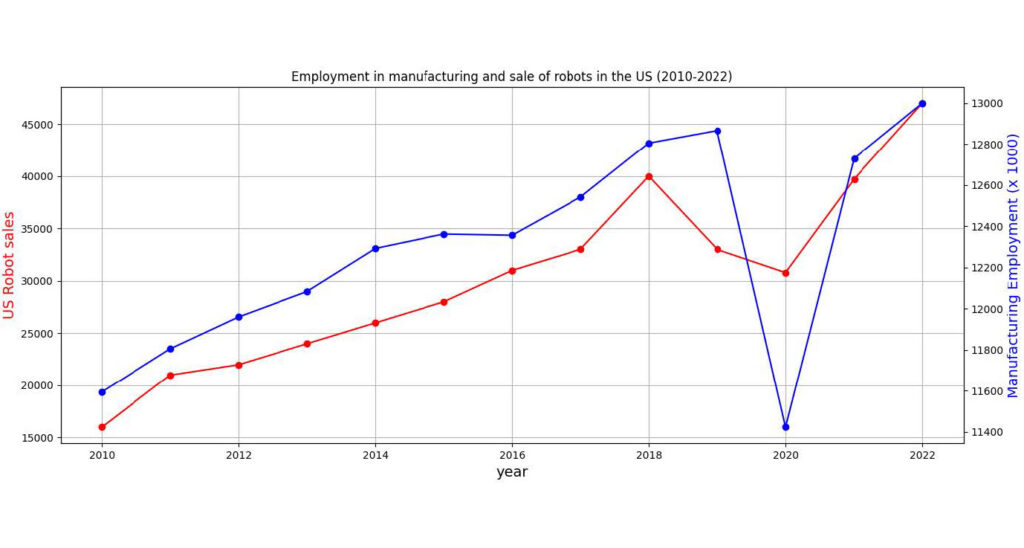

The latest robotics roadmap said both automation and employment lead to economic growth, as shown by data from the International Federation of Robotics and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Click here to enlarge. Source: “A Roadmap for U.S. Robotics”

The U.S. can regain robotics leadership

When do you think that might turn around? What needs to happen?

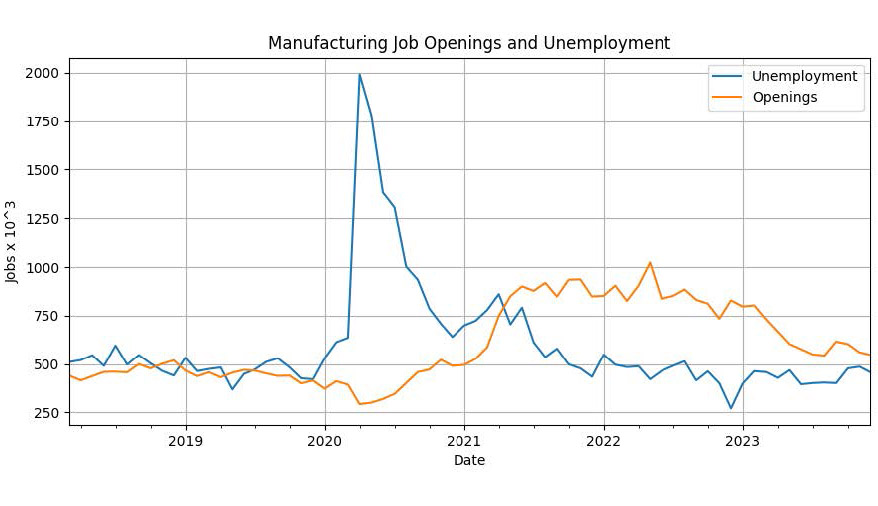

Christensen: In the second half of the year, robotics could pick up quickly. More things, like semiconductors, are moving back to the U.S., and manufacturing and warehousing are short by millions of workers.

Reshoring hasn’t happened at scale, and there’s not enough R&D, but the U.S. also needs to retrain its workforce. There are a few trade schools with a robotics focus, and we need the federal government to assist in emphasizing the need for retraining to allow more reshoring.

What other enabling factors are needed in Washington?

Christensen: The OSTP [White House Office of Science and Technology] had limited staffing in the previous administration, and we can’t afford another two years of that. We need to hold Washington accountable, and the U.S. industrial sector needs agility.

The robotics community has a big challenge to educate people about the state of the industry. Americans think we’re better than we actually are. We’re not in the top five automotive producers; it’s actually China, Japan, Germany, South Korea, and India. No major industrial robotics supplier is based in the U.S.

When we started these roadmaps, the U.S. was in the top four in industrial robot consumption and a leader in service robotics. Now, it’s no longer in the top 10.

The future for iRobot, the only U.S. household name in robotics, isn’t pretty after its deal fell through with Amazon, at least partly because of antitrust scrutiny. We need to assist our companies to remain competitive.

How might the U.S. get its act together with regard to robotics policy? Australia just launched its own National Robotics Strategy.

Christensen: We shouldn’t let robotics go. I left Denmark about 30 years ago, and the robotics cluster there started after Maersk moved its shipyard to South Korea. The city of Odense and local universities, with national government support, all invested in an ecosystem that led to the formation of Universal Robots and Mobile Industrial Robots. Today, Odense is the capital of robotics in Europe.

Recently, the Port of Odense launched a robotics center for large structures. It continues to grow its ecosystem. It shows why it’s worth it for nations to think strategically about robotics.

We’re in talks to revitalize the Congressional Robotics Caucus and with Robust.AI. We can also show how the advances in AI can help grow robotics.

Manufacturing job openings currently exceed unemployment rates. Source: BLS.gov

Tell Us What You Think!