|

Listen to this article

|

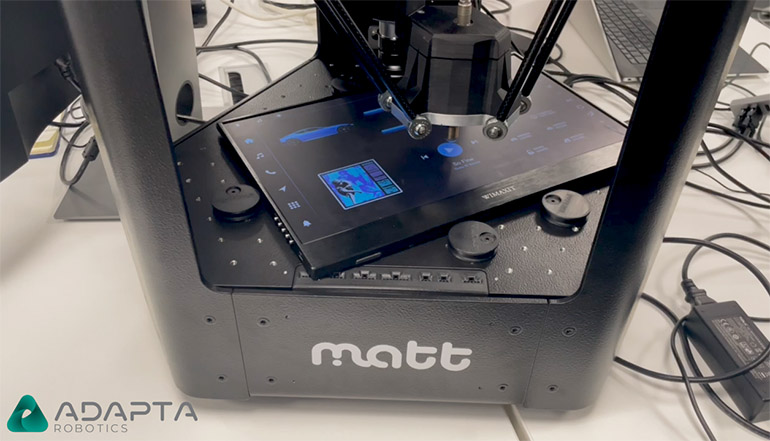

Adapta has developed robots for specific use cases. Source: Adapta Robotics

Starting a robotics company is always challenging, as inventors and entrepreneurs scramble to get access to capital and tap the local talent pool. However, identifying the right applications and markets is a good place to begin, according to the co-founders of Adapta Robotics & Engineering SRL.

The Bucharest, Romania-based company said it specializes in addressing challenges in settings where traditional automation has fallen short and in use cases that have been overlooked. Adapta’s model includes a one-time robot purchase fee, plus annual license and maintenance fees.

In 2017, the company’s founders developed the first prototype of MATT, a delta robot for device testing, at rinf.tech with European Union support. In 2021, they branded Adapta and developed the Effective Retail Intelligent Scanner, or ERIS, for scanning items on store shelves. In 2022, Adapta became an independent brand.

Mihai Craciunescu, co-founder and CEO, and Diana Baicu, co-founder and lead robotics engineer of Adapta Robotics, spoke with The Robot Report about the company’s approach to designing and customizing robots for applications that were previously difficult to automate.

Adapta Robotics started with competition team

What is the origin of Adapta Robotics?

Craciunescu: Cristian Dobre, Diana, and I started the company in 2015, but we had been a group in the University Politehnica of Bucharest, the largest technical university in Romania, starting in 2012. Our goal was to create robots for competitions, and we participated in competitions from Europe to Turkey to China.

We won most of them, and we’ve built line-following robots, sumo robots, and self-driving cars in a small scale for Continental. We then said, “OK, what’s next?” We had to choose between pure research in academia or starting a robotics company, and we wanted the more applied side of robotics, based on our success in those challenges.

How did you determine what tasks or applications to try to automate? As we saw at R-24 and other events, there are already a lot of robots out there, from disinfection to materials handling.

Craciunescu: Our first idea, the MATT testing robot, came totally by chance. We were exposed to a U.S. manufacturer that did its software development and testing in Romania before pushing updates to its whole fleet of mobile phones. Phones in the Asian market were a testing ground for it, and all of its software testing processes were automated.

During one test, the screen went blank, but behind the scenes, the processor was still doing the right tasks. The company didn’t catch it, and millions of phones went blank. Knowing about this issue and having the robotics experience we did, we said, “Why don’t we build a robot to test these phones?”

Then, we slowly saw similar needs in other industries like automotive manufacturing. Infotainment systems need to be tested, and automakers want to make sure everything works as intended. Many other use cases derive from that.

We identified the problems and clients, and then we did a bit of market research. There were a couple of competitors, but they were very expensive and had limited capabilities.

How did you arrive at inventory with ERIS?

Craciunescu: We had a client with a couple of issues in its stores. One, some products had labels showing the wrong prices.

Another was that [the retailer] knew from its systems that it had a certain amount of products in stock, but it did not know if those products were on the shelf or in the warehouse somewhere. If they’re not on the shelf, that means lost opportunities.

The company was aware of the solutions on the market, including inventory robots from the States, but those were too expensive for the task it wanted to do. And, if you scan a shelf with an autonomous robot, and you have a report that 20 labels are wrong, you still need a human to manually replace the labels.

The company didn’t care about the autonomous part; it just wanted the problem to be fixed, so we have a scanner on a pushcart. We focused on reading the labels correctly, detecting the products that are out of stock or soon will be, and creating a report on just those three features.

We’re also exploring other functionalities like planogram compliance, making sure the products are placed where they’re supposed to be, while checking if you have multiple labels of the same product displayed on the shelf. But that was the main idea: Create a relatively cheap solution to scan the shelf and give you an audit.

Adapta founders, from left: Cristian Dobre, Mihai Craciunescu, and Diana Baicu. Source: Adapta Robotics

Know thy customers

Were you developing these systems for specific customers, or did you already have broader applications in mind? Did Adapta Robotics develop them with multiple customers at once, or did you start with one customer and then branch out?

Craciunescu: It was mixed. As an engineer, you can design all kinds of robots. Our approach is to try to solve problems that are specific to a certain industry.

Having the client tell us what they need is the most valuable feedback. We could think of different solutions in our lab, but when you are doing that in real life, you can quickly see what things to focus on.

It’s very important to have a client in the loop when you design something. Ideally, you should have more than one, but as we got started, we needed at least one to can use, let’s say, the first version of the robots. It can see what doesn’t work, and then you can improve on that. After you have a prototype, then you can look around in the market.

Baicu: When we’re getting this information from clients and designing a product, we try to make something more general that can be easily customized afterwards. You don’t want it customized from the beginning because that limits other possibilities, even for the development for that customer.

But then you need first customers that are patient, right? They have to be willing to work with you and understand that not everything’s going to work right away.

Craciunescu: That would be the ideal setup. Some clients were really pushy, and it was up to us to deliver. They can understand that something doesn’t work, but we had to fix it as soon as possible. We had quite a bit of pressure.

The MATT delta robot for product testing. Source: Adapta Robotics

Co-founders share lessons learned

The robotics development process is rarely a straight path. What are some of the lessons that you learned or surprises along the way?

Baicu: We know this from when we were building competition robots, but it became even more clear [with Adapta Robotics]. It’s about the design choices overall. … You need to have the right components and architectures from the beginning, at least with durability and scalability in mind, because otherwise, it will be very complicated to modify everything rather than just thinking about it from the beginning.

Of course, there’s a balance between how far you can go in these choices. Very expensive components or very complicated architectures take more time to implement and more money.

When you’re sourcing components, whether it’s sensors or actuators, do you have preferred partners? How did you identify what would work best, given your and your customers’ priorities?

Craciunescu: It’s an iterative process. Let’s take ERIS as an example. Initially, we made an educated guess about the best-in-class cameras we needed.

When we actually connected them to the computer, we saw that they were on USB 3.0. We had the right cameras, but the communication protocol made the processor waste a lot of time converting the serial information to actual pictures and data metrics you could use.

We wanted that processor to run other things, so the next step was to find some cameras on another protocol. We then looked at different distributors and so on.

Another aspect we did not have experience with was, for example, cameras to measure the distances. Our approach was to buy depth cameras from all the major manufacturers and test them internally. We had a couple of criteria — we knew we wanted to look at shelves that were up to 1 m in depth and knew the distances from the robot to the shelves.

We also looked at the company maturity, or if they could provide the cameras 10 years from now. If we’re happy with all these smaller decisions, we’ll pull the trigger.

If you know from prior experience what’s the right solution for you, that’s fine, but most of the time, you need tests to validate the right path. This makes R&D quite expensive, but sometimes, you don’t have the luxury to buy all the solutions out there.

The ERIS inventory-scanning system works with human associates. Source: Adapta Robotics

When to focus on integration and simulation

On the software side, Adapta Robotics’ customers may use different systems. How much work does integration involve?

Baicu: It’s a significant part of what we do. There’s a focus from the beginning on our side to create the software infrastructure and the intelligence as well, meaning the computer vision and algorithms, or machine learning and AI. It’s a process that needs to be supported.

First of all, there are the updates to improve or fix bugs, and at the same time, we maintain the algorithmic part with new data sets, examples, or retraining if needed.

How much do you rely on simulation for training and deployments?

Craciunescu: We try not to rely too much on simulation. We do some — for example, for mechanical stress testing. But we don’t go into the details like kinematics. We do what makes sense from an engineering point of view, as we want to build an actual product.

You can focus a lot on simulation, and that can be a trap because you can make the most beautiful simulations in the world and not have a product.

Baicu: At the same time, you can transpose simulations into real-life situations. The simulation is an idealized environment, so you have to introduce noise or variations, but it will never be the real world. Sometimes, it can be very complicated if you put too much effort on the simulation side.

Adapta gives a glimpse of its roadmap

What is Adapta Robotics planning for this year?

Craciunescu: MATT is designed to be flexible and for multiple use cases. This year, we’re looking at specialized versions of MATT for different industries, like refurbishment, automotive, and medical.

It’s currently used in those industries with add-ons, but there are not models specifically designed for each industry, which could help the selling process.

Are you focusing more on productizing or re-engineering your technology? For instance, MATT’s software suite now works with a six degree-of-freedom robot arm.

Baicu: A bit of both. We now have clients and know their needs. Maybe we just present it differently or add some features that make the product easier to set up and use. Sometimes, it’s about creating new add-ons or complementary solutions that can respond to the needs in that field of activity.

Craciunescu: With ERIS, we already have a client that’s mostly in the logistics space and requires things like detecting of barcodes. It’s similar to retail but a different application. We’re exploring ways of reusing parts of the hardware and software that we’ve developed.

Are you in the midst of fundraising? Are you looking to expand to new markets internationally?

Craciunescu: Yes. We’re in the process of raising capital and are in a due diligence phase. We’re currently at 10 highly skilled professionals, but capital would allow us to be more aggressive in markets such as automotive.

Currently, 50% of our clients are in the U.S., and the rest are Western Europe. We have a couple of clients in India and Brazil as well.

At R-24, we discussed the Danish robotics scene. What is the industry like in Romania?

Craciunescu: Denmark is an outlier, and it’s doing very well. The European market in general doesn’t encourage R&D, which is very cash-intensive. If you look across Europe, robotics requires funding from the EU and from each individual state.

There are other robotics companies in Romania, and we have a lot of talent locally. We sometimes find out about one another at events outside of Romania.

Baicu: Romania is quite well-developed on the IT or software development side. It’s fairly complicated to have a discussion for what the needs are for a company that does hardware.

With the rise of AI, we need to have a deeper consideration for what we are putting our efforts into. We’re now seeing a bit of a shift, and are seeing a better attitude toward manufacturing and hardware.

Craciunescu: The brain drain really affects us. As a young student willing to learn about robotics, I had no mentors. That’s a problem for the medical industry as well and society as a whole.

Right now, we’re trying at Adapta to provide a space for new students to come and learn from professionals. We had the option of going abroad but decided to build something locally. Being part of the EU, we can basically scale up anywhere we want.

Tell Us What You Think!